Porting an Android App to Flutter

Photo by Andrea Reiman on Unsplash

Between our scholarship programs, free and paid students, and various localizations (Arabic and Chinese), A LOT of students have taken our flagship Developing Android Apps course. And that means they have seen the source code of Sunshine, the example weather app, making it likely one of the most widely examined Android apps on the platform.

As a known quantity and point of familiarity, I thought Sunshine would be perfect to port to Flutter to test out the framework.

Getting started

Getting Flutter doctor and the plugins installed was quick and easy thanks to helpful multi-platform instructions.

Sunshine has three app screens:

a Home screen showing the two weeks of weather conditions and high/low temperatures,

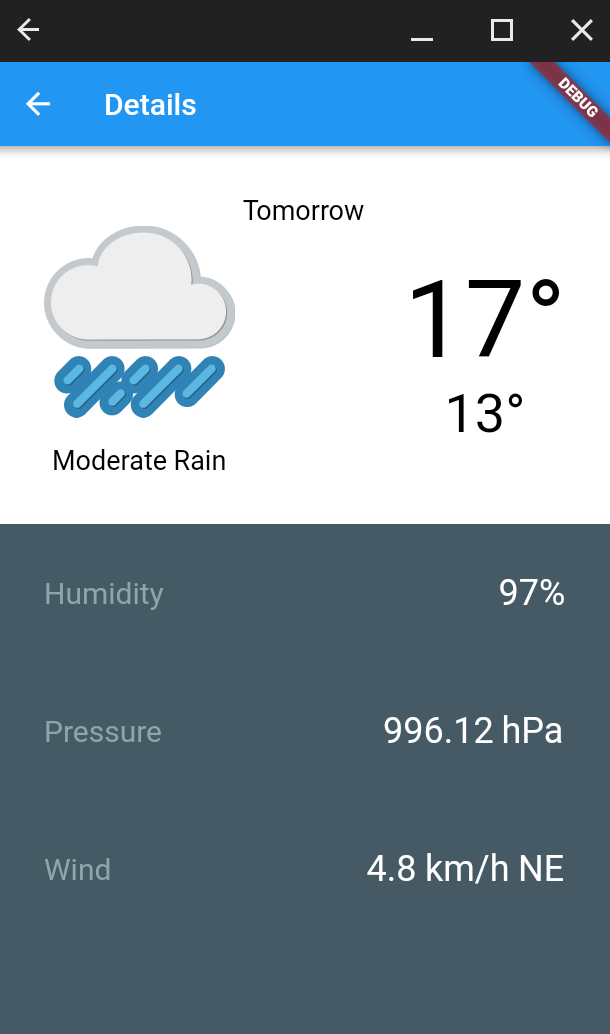

a Details screen pops up with wind conditions, pressure, and humidity,

and a Settings Screen, for selecting temperature preference, not implemented in this version.

Designing the DetailsScreen

I started with the DetailsScreen because there was less on the screen to layout. Building this screen was where the hot reload in Flutter really had the chance to shine. I created the screen using unstyled text and slowly added colors and paddings.

Padding was one of the first areas that left me a bit stumped. Unlike Android where you can add an arbitrary padding/margin on almost any View, in Flutter, you need to wrap your Widget in a Padding.

Widget createSensorListView(BuildContext context, String label, String data) {

var row = Row(

mainAxisAlignment: MainAxisAlignment.spaceBetween,

children: [

Text(label,

style: TextStyle(

color: Color(0xFF90A4AE),

fontSize: 20.0)

),

Text(data, style: TextStyle(

color: Colors.white, fontSize: 24.0))

]);

return Padding(

padding: EdgeInsets.all(32.0),

child: row,

);

} Organizing things in Rows and Columns was pretty straightforward and easy to reason about. But like Padding, it was surprising where some common properties lived. To set width, height, or a background color, I had to wrap my Row or Column in a Container.

Another nit was text. Having to create a TextStyle widget to style a Text widget wasn't so bad. After years and years of having dp and sp (device-independent pixels and scale-independent pixels) beat into me, it was a little odd to have fontSize based on pixels. Also if you are specifying a custom Color that isn't already defined in the Colors widget, the constructor takes a hex value in AARRGGBB format. The Colors class implements the color spectrum from the Material Design spec so use that if at all possible.

Designing the HomeScreen

The HomeScreen was a general ListView with slightly different widget trees depending on if the weather was for today or another date.

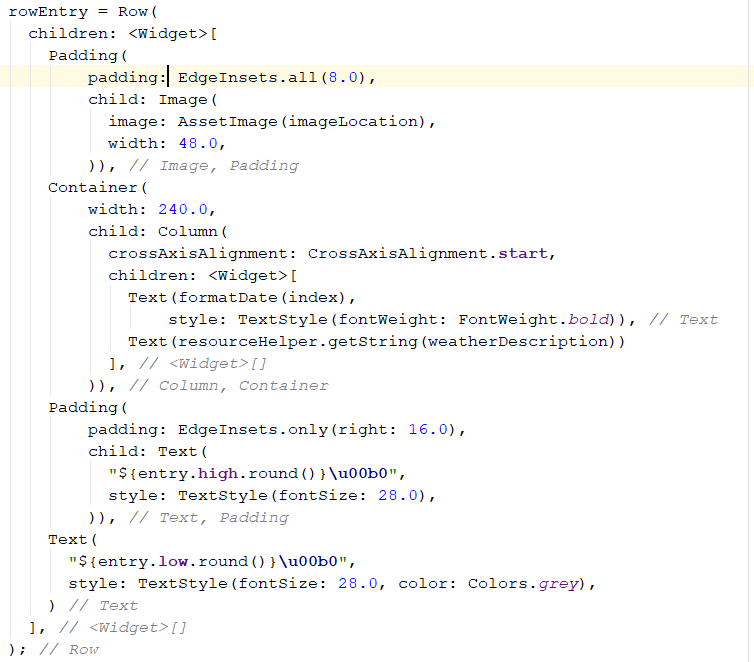

The code to make each entry did get a little complicated but to Flutter's credit, the Android Studio plugin overlays comments in real time to show which closing parenthesis or brace corresponded to what. Despite this, for readability sake, I probably wouldn't go more than a few levels deep without spinning out some of the code into a new function.

The image above (code here) is the body of the _createWeatherRow function and body property in Scaffold, served the same sort of purpose as an Adapter, an ArrayAdapter in this case.

Widget createScaffold() {

return Scaffold(

appBar: AppBar(

title: Image(

image: AssetImage('assets/ic_logo.png'),

fit: BoxFit.fill,

width: 100.0),

),

body: ListView.builder(

shrinkWrap: true,

itemCount: weather_items.length,

itemBuilder: (context, index) {

return _createWeatherRow(weather_items[index], index);

}),

);

} A State of Mind

Flutter has two high level classes from which you'll extend your app screens: StatelessWidget and StatefulWidget. StatelessWidget is a bit of a misnomer because it's not that it can't hold state, the state it holds just can't be modified. It's more or less final after being created. My DetailsScreen is a StatelessWidget because it doesn't need to change after being initialized. The HomeScreen will need to load weather data from the web and the contents of that screen will change several times in the lifetime of a single run so it is Stateful.

StatefulWidget depends on a State object to well,... manage State. createState is called when the widget is inserted into the widget tree. initState handles any initialization code, in our case, the HTTP request that we'll see in the next section. setState operates like a notifyDataSetChanged and tells the framework to schedule the widget tree of that widget to be rebuilt.

Seeing into the Future

To handle delayed computation, Flutter uses Futures (also known as Promises or Deferred in other languages). You can chain a number of then blocks to a Future for further processing, catchError blocks to handle errors, and assign timeouts.

The result is some really compact code like this little bit to load JSON from a web service, pass it to a function to process it into objects and finally store them in the screen's state.

@override

void initState() {

super.initState();

var url = "http://andfun-weather.udacity.com/staticweather";

http.read(url).then((response) {

setState(() {

weather_items = weatherHelper(response);

});

});

}

Prior to LiveData in Android, getting remote data and keeping the UI performant and up to date meant using a Loader of some sort.

One of the shortcuts I did in my Flutter version of Sunshine, was choosing to use the strings.xml file from the original Android version to get my weather conditions strings. This introduced a race condition where the strings needed to be loaded before attempting to initialize the app. To handle this case, I used a FutureBuilder.

FutureBuilder allows you conditionally return a Widget based on the state of the Future. In my case, it was the ResourceHelper future I created. If the future hadn't started the async computation (ConnectionState.none) or had started but is waiting (Connection.waiting), the screen populates with a text widget. Otherwise, (ConnectionState.done), it creates the scaffold and UI for the screen.

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

// Delay UI until the ResourceStringHelper has finished loading

// it uses Futures/async

return FutureBuilder(

future: resourceHelper.getFuture(),

builder: (BuildContext context,

AsyncSnapshot snapshot) {

switch (snapshot.connectionState) {

case ConnectionState.none:

case ConnectionState.waiting:

return Text("Loading...");

default:

return createScaffold();

}

});

} FutureBuilder uses the widget's underlying state to do the updates.

It's worth noting that my resource file is local so I don't have to worry about long delays as I would with a network resource. If a more substantial part of the app depended on HTTP, I might use the loading time to perhaps draw the last stored data or mock out more of the screen.

Internationalization and Resource Strings

It wasn't until I started writing up this post that I learned of the way Dart handles internalization and localization. Surprise surprise, it's all in code. If you have used ResourceBundles in Java, the general flow is similar, you create functions that use the Intl library and return the appropriate string. It has great support for conditional gender or plural language.

Here's an example from the documentation:

howManyPeople(numberOfPeople, place) => Intl.plural(

zero: 'I see no one at all',

one: 'I see $numberOfPeople other person',

other: 'I see $numberOfPeople other people')} in $place.''',

name: 'msg',

args: [numberOfPeople, place],

desc: 'Description of how many people are seen in a place.',

examples: const {'numberOfPeople': 3, 'place': 'London'}); I think it's great to be able to handle so many cases but it's a little concerning to have this be in code. Translators are not necessarily technical and in many cases, they work from the equivalent of a JSON or flat properties file. Integrating so much of the localization into code seems to open up the possibility of accidental code changes by non-developers. I really would have liked a option like Java properties file backed resource bundle.

Check out the code for the ported app here: https://github.com/jwill/code-samples/tree/master/sunshine_flutter.

Final Thoughts:

Flutter was a mixed bag for me. I think your mileage will vary depending on how much Android experience you have and if your app needs to look like idiomatic iOS and Android versus having a unique look and feel across the platforms. Dart's closeness to Java made the language syntax a breeze. But its differences from established norms in Android made some areas really maddening.

There were definite bright spots, places where using Flutter was truly delightful. Despite constructing a widget tree in code, it was less overall code to get a ListView working. Adding a ripple by simply wrapping a Widget in an Inkwell and make it launch a new screen on clicks by adding a function to onTap, kinda genius. Iterating on the design of a screen in almost real-time was another plus. However when you did something wrong, the stacktrace got pretty gnarly.

The core of Flutter is really light so you need to add a dependency for many things. That's good because it keeps cruft out but I didn't expect to need a package in order to do HTTP requests. I do however appreciate the scores that dartpub gives to libraries based on their Popularity, Health, and Maintenance. Even though I had to search for more packages than I liked, I did feel secure that I wasn't picking things that were being used by only one person or based on a shaky version of the API.

I'm concerned about how this affects cross platform development. It's not common for someone to be proficient in both Android and iOS. I fear that there will be plugins that work perfectly on one platform but not as well on the other. Lag on the iOS side for changes to hit Flutter is a concern. I worry about divergent lifecycles like my colleague Nate discussed in his retrospective on React Native usage at Udacity.

Doing your whole widget tree in code doesn't feel as adaptable to multiple screen sizes. I did see a couple of percentage based widgets in the spec but I wasn't able to get them working at coding time. I chalk it up to being between beta versions as an update was happening. When it does specify a dimension, the documentation uses simply pixels in most places for dimensions so at first glance it looks like physical pixels. After some digging, there's a mention of logical pixels, basically a dp. Having the units a little more forward would be helpful, the Flutter for Web Developers section was another thing that made me think it was physical pixels being used.

I'll definitely use Flutter in the future but I'm not sure if it will be production app development. It has a lot of promise for me as a prototyping tool to get a not-quite high-fi version of an app into tester's hands or for a demo that is a bit more tactile than Keynote slides or InVision.